Submitted by: Matthew A. Werner

Robert Sirko likes to talk. He also likes to think and read. He does all three in abundance. He is inquisitive and creative. His insatiable curiosity has shaped him. He is an academically trained artist. He marvels at life and the human mind. He has a lot on his mind and he really wants to share it. He can throw a lot at you, but hang in there. You’ll learn something. You can’t help it. He’ll teach you something. He can’t help it. He has a lot of stories to tell—funny stories, thoughtful stories, tragic stories. He will die from cancer. Robert Sirko has a lot on his mind.

Sirko grew up in Gary, the son of a steel worker. He held his first art exhibit at age 6—he was into dinosaur art then—and his parents toured the gallery in his bedroom. “Ah, very nice,” his father said. His mother offered constructive criticism. “Shouldn’t this one’s neck be a little longer?” she asked. He kept drawing. As a teenager, he had a makeshift art studio in his parents’ basement. He was working on his art one night after midnight when his father got home from his shift at the mill. His father came downstairs. He had had a particularly bad night, Sirko could tell. They made small talk. His father looked at Robert’s newest drawings and said, “I don’t want you to work in the mills. I want you to do this.” Exhausted, his father carried himself upstairs and went to bed. That conversation etched in Sirko’s mind and cemented his future.

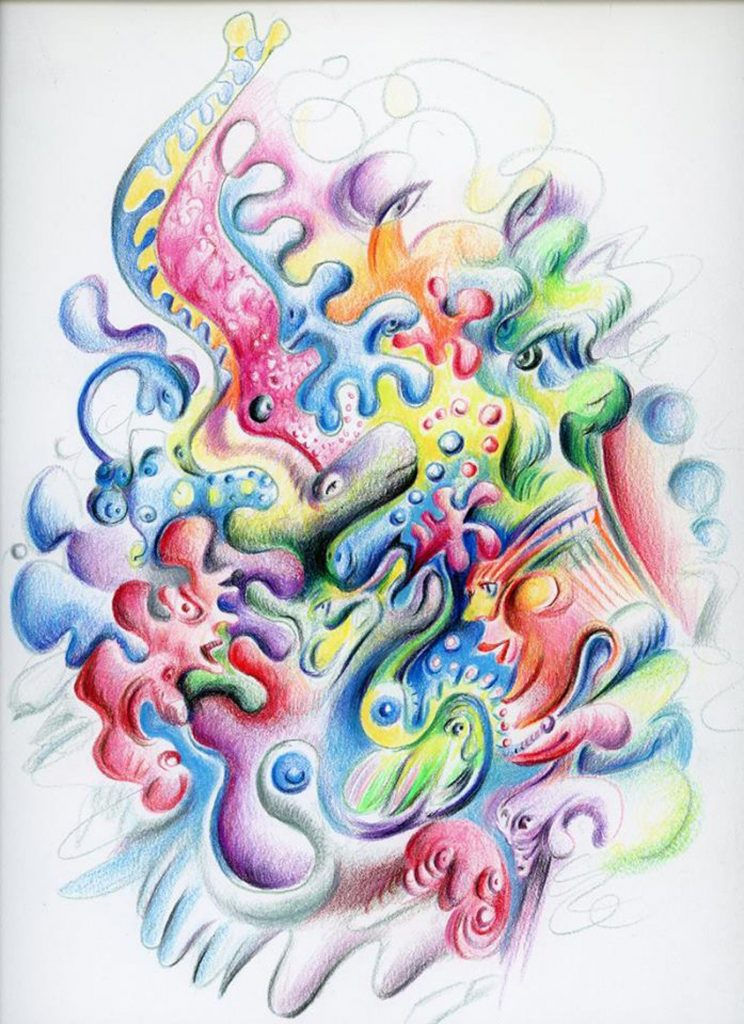

Cancer Drawing 1

Sirko earned a Bachelor of Arts at Indiana University and a MFA from the California Institute of the Arts. He has spent years in graphic design where he concentrated on space, layout, messaging, and typography. He has taught at Valparaiso University for twenty-eight years. Inside him, he always carried a flame for painting and drawing. Nine years ago, he turned fifty and wanted to get away from corporate and commercial work. So, he grabbed a canvas and some paint and went to work. The exercise thrilled him. Each canvas became a new discovery. A new learning experience. The paint took him on a wild and fun-filled adventure that challenged and excited Sirko’s mind and spirit.

His paintings have a level of alchemy to them. “I move the paint around on the canvas and see where it takes me,” he said. He looks at the colors and the lines he’s drawn and the sketch he mapped out. The deeper he dives into the work, in that moment, the more he is taken away. Obsession moves in. He’s in the zone. Hyper-focused. Mentally, he’s in that space, exploring and digging, discovering new visions. Things change. He adds figures, subtracts others, lines grow beyond their original border. He makes it linear, but deviates just enough on the left and the right to keep the viewer looking and looking. He becomes entranced in his work—thinking, exploring, learning, painting, imagining.

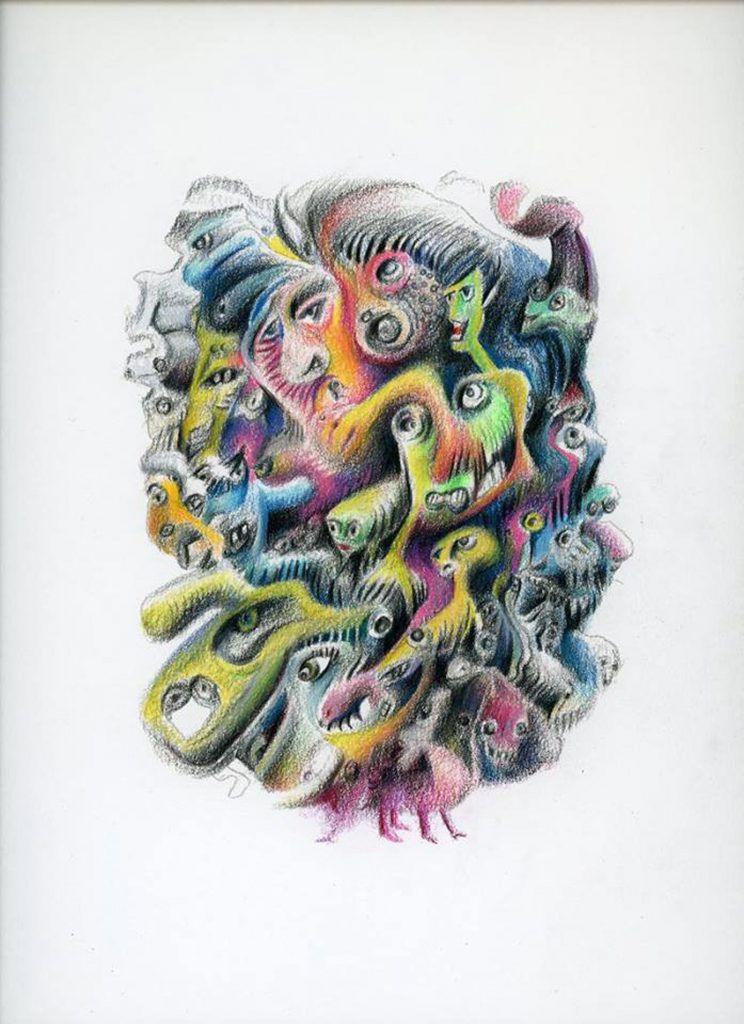

Cancer Drawing 7

Each painting becomes a unique learning experience. When he dips a brush into paint and touches the canvas, the outcome is unknown. Sirko admits that is a big part of the fun and challenge—the unknown—the mystery of the outcome and the multiple phases he will go through to reach it. “Painting is a great teacher,” he said. “For me, it’s why they tend to look psychedelic. I try to learn from my paintings. I let them take me some place. It’s a lot like life—the struggles, the elements of chance and exploration, stretching your boundaries, learning your limitations. The experience teaches.”

When he paints, he reaches into his subconscious. “When it’s clicking, I’m a zillion miles away,” Sirko said. He can become so ingrained in his work, that he is unaware of the outside world. “Your mind is taking you elsewhere. It’s getting you out of your daily hum-drum. Getting to a new place. There’s something innate about the subconscious that beguiles you to do it.” When his wife or one of his kids enter his studio to get his attention, they have to yell or touch him on the shoulder to get him to snap out of it.

His art reflects his insatiable curiosity. It reveals the years he spent appreciating and studying mythology, fantasy, great story telling, Native American art, world religions, the human mind, and more. Vibrant colors explode from the canvas. Greens, and reds, and yellows, and blues, and oranges, and purples, and pinks. The paint shouts at you, but don’t be intimidated. You can’t be intimidated. Step up. Lean in. Look closer. There, in the lines and shapes, is a wicked jackalope with rainbow ears that rise like whipping flames. His work revels in the mystic and the mythical. Psychedelic roosters flank the right and left, as do blue coyotes grinning like Cheshire cats. An ocean horizon. A celestial eye. A majestic frog overlooks the whole scene and conjures thoughts of the Bufo alvarius, a toad whose secretions are known for their psychedelic effects. Sirko pointed out with a laugh that’s the same toad Homer Simpson once licked in an episode and tripped out.

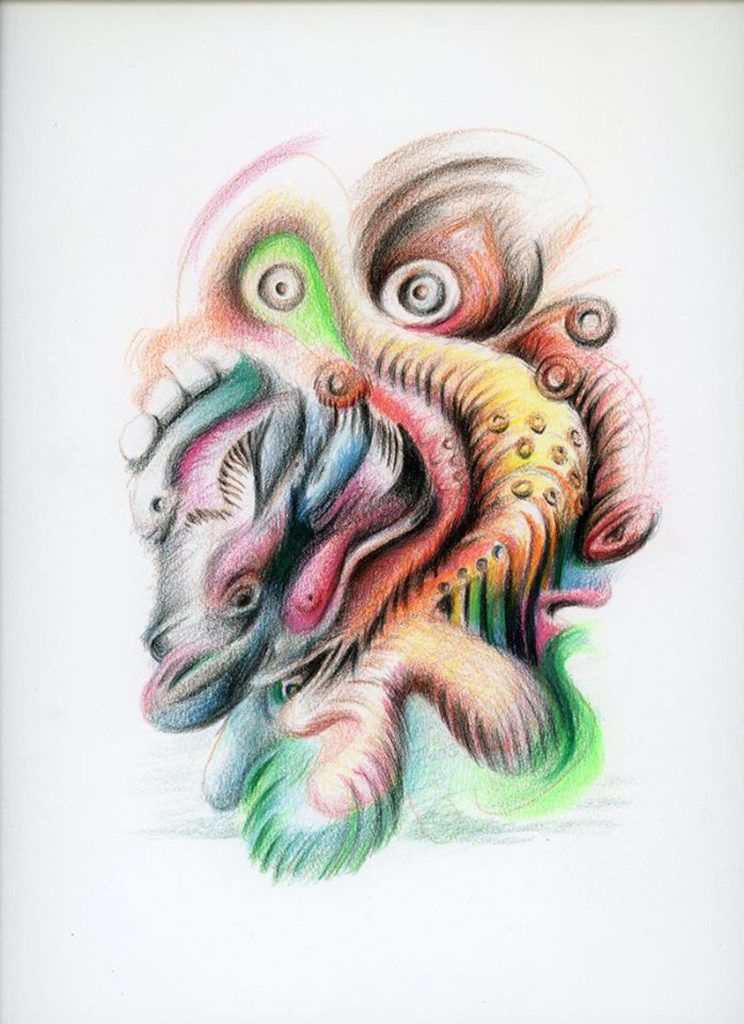

Cancer Drawing 11

Every one of Sirko’s paintings contains a touch of whimsy (his dream job once was to write for National Lampoon magazine), but there’s serious art and an incredible amount of thought tucked into every piece. This one captures a moment in time in ancient history, Sirko explained. It encourages you to think a lot about belief. The more he talks and the more I look, I can see it and a whole lot more. The colors, the lines, the imagery—it’s focused and yet there’s a lot going on.

I look at other paintings filled with space ships, smiling, laughing, scared faces, damaged faces, happy faces. There’s a dragon. Here’s a fish. Shapes crawl right up to you and expand far into space, deep beyond the oil paint on the surface. Every time I look, I find something new. Each time it’s spectacular, wonderful. Look there. An eel, a hand, a waterfall, a man, creatures real, creatures imaginative, a porpoise, a planet, an insect. It’s a show playing out in front of you on a five-foot canvas. Wow. Wow! I caught myself smiling.

That’s what his work is all about: discovery and rewarding the viewer for looking. The longer you look, the more it reveals. You only need your eyesight, imagination, and a willingness to participate. He is interested in what you see and what you take away. He wants you to explore it. “I like to keep viewers involved as long as possible and hope they see a narrative,” Sirko said.

I shared a photo of Sirko’s painting with a friend. “Wow, that guy dropped a lot of acid in his day,” he said. Actually, no—he has never taken any psychedelic drugs. My friend couldn’t believe it.

For years, Sirko has ruminated on the human mind’s capabilities and how it works. When his mother had Alzheimer’s, he marveled as she wove the current moment, fifty year old memories, and an imaginative component into her conversations. He wondered where it came from. Many people compared his paintings to psychedelic art and pressured him to try psychedelic drugs. They told him it would be a life-changing experience. He acquiesced and scheduled a trip to South America to experience ayuhuasca for the first time when illness struck. Cancer. Mantle cell lymphoma. Sirko’s physical condition deteriorated quickly. He lost weight. He could barely walk. His body emaciated. He cancelled the trip.

Beneath the Luminous Tree

A year ago in mid-July, Sirko started hyper-CVAD chemotherapy. Aided by his wife (his savior who is stronger than words can describe), he made the slow, painful walk to the car, rode to Chicago, and entered Northwestern Memorial’s oncology department. That first night in the hospital, he took out colored pencils and a sheet of paper. He wondered, “what would cancer look like?” Then he drew what he later called his Beasties. Forty more drawings followed over the next seven months and Sirko dubbed them his Cancer Drawings.

The act of drawing took him away from thinking about other things. “Drawing was a respite from all that,” Sirko said. The weakness, the pain, the hair falling out, the sickness, the body’s demise, the thought of death hovering. “I didn’t think about a purpose or intent when I drew. I laid my hand down on the paper and let it wander.”

His drawings are not about fear (although it is present). Looking at the forty-one drawings, you can see good days and bad days. Anger, fear, frustration, poking, prodding, staring eyes, the endless questions, the well-wishes, anxiety, love, and wonderment. Just drawing, drawing, drawing. Going away, going inside himself, entering the space on the paper, drawing where he was in that moment. It was an opportunity for him to hone his skills, to express himself, and to cope the best way he could—through art.

“In some perverse way, I looked forward to it. I knew I was in good care, had time on my hands, and I couldn’t sleep, so I was in some altered mental state,” Sirko said. His drawings tapped his subconscious. “If you think ayahuasca can change your life, try cancer!”

Each one took six to eight hours to complete. Each one tells a different story. Each one draws you in. True to Sirko’s work, there is a bit of whimsy present and most of them explode with color.

“I didn’t want to work with a finale associated with the Cancer Drawings because then I would believe there was a finale,” Sirko said. Mantle Cell Lymphoma can be managed, but there is no cure. “People in my situation—I could live two years, or I could live ten. Every morning I wake with that hanging over my head. That’s why I’m so passionate about my art.”

123 billion miles in search of Persephone

The scariest part is the unknown. His life has become his art and his art is now his life.

Don’t pity Robert Sirko. He knows what he’s up against. A single bug bite sent his immune system reeling and he landed in the hospital for five days. This is his new normal. He’s working through it. While painting one day, he heard a mosquito buzzing. He didn’t cower in fear. He hunted it down. “Where are you, you SOB,” he called out. THWAK! “Aha! You thought you could get me!” Then he laughed and continued painting.

Robert Sirko is feeling better. He’s starting to fall into old habits like drinking coffee every morning (he makes a mean cup). He knows he must be disciplined—eat healthy, be healthy. He will keep putting colors on canvas and paper. He has stories yet to tell and passion yet to share. He makes art because he has to make it. It’s inside him, begging to be set free.

Last fall, Saint Lawrence University in New York held an exhibit filled with renowned artists Alex Grey, Donna Torres, Rick Harlow, and Andersen Debernardi. Right with them hung the art of Robert Sirko—son of a steel mill worker, a local guy who grew up here and lives a short drive from the Lake Michigan dunes.

Do not settle for a photo of his artwork on a phone or a computer. Experience them first hand. His paintings and all forty-one Cancer Drawings are on display at The Nest (803 Franklin Street, Michigan City). But you’re running out of time—the exhibit is closing soon. The last day is Sunday, July 30 and there will be a grand finale party starting at 12:00 pm. Sirko will be there. He’d love to talk to you, or leave you to explore on your own. Grab a friend, your kids, or come alone. Step up. Lean in. Explore. Discover. Then feel the creases in your face as your subconscious draws a smile. Event information can be found here.

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

Comments